Great ATLANTIC Hurricane of 1944

September 1944

Quick Facts

Storm Type | Cat. 2 Hurricane

NC Landfall | Hatteras

NC Wind Speed | 110 mph

NC Storm Surge | no data

NC Rainfall | no data

NC Pressure | 27.97 in

Total Deaths | 389

NC Deaths | 1

Total Cost Then | $100,000,000

Total Cost 2018 | $1,423,556,818

About this storm

September 14, 1944 The second hurricane of 1944 to strike North Carolina brought death and destruction to 900 miles of coastline from Cape Hatteras to Newfoundland. The Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944 approached the Outer Banks on the morning of September 14 and passed just east of Cape Hatteras on a track toward New England. The eye of the hurricane remained off shore, and North Carolina’s coast was spared a direct hit. But as the great storm moved northward, its forward speed increased, and it slammed into Long Island, New York, at about10:00 P.M. the same day. The damage was heavy in New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Maine.

The pattern of destruction of the ’44 storm was very similar to that of the Great New England Hurricane of 1938. The ’38 storm still ranks as one of our nation’s worst natural disasters. The American Red Cross reported that it claimed 494 lives (plus more than 100 who were lost at sea), destroyed over 4,000 homes and buildings, and brought $350 million in Damages to the north-eastern states. Although the 1938 hurricane brought no serious effects to North Carolina, it did blow by Hatteras and then accelerate to the north, reaching an incredible speed of 56 mph. This meteoric movement intensified the storm’s effects on the New England coastline, and the hurricane’s surge drowned scores of coastal residents. During the 1938 hurricane, one of the highest wind speeds in U.S. history was recorded in Milton, Massachusetts- a gust measuring 186 mph.

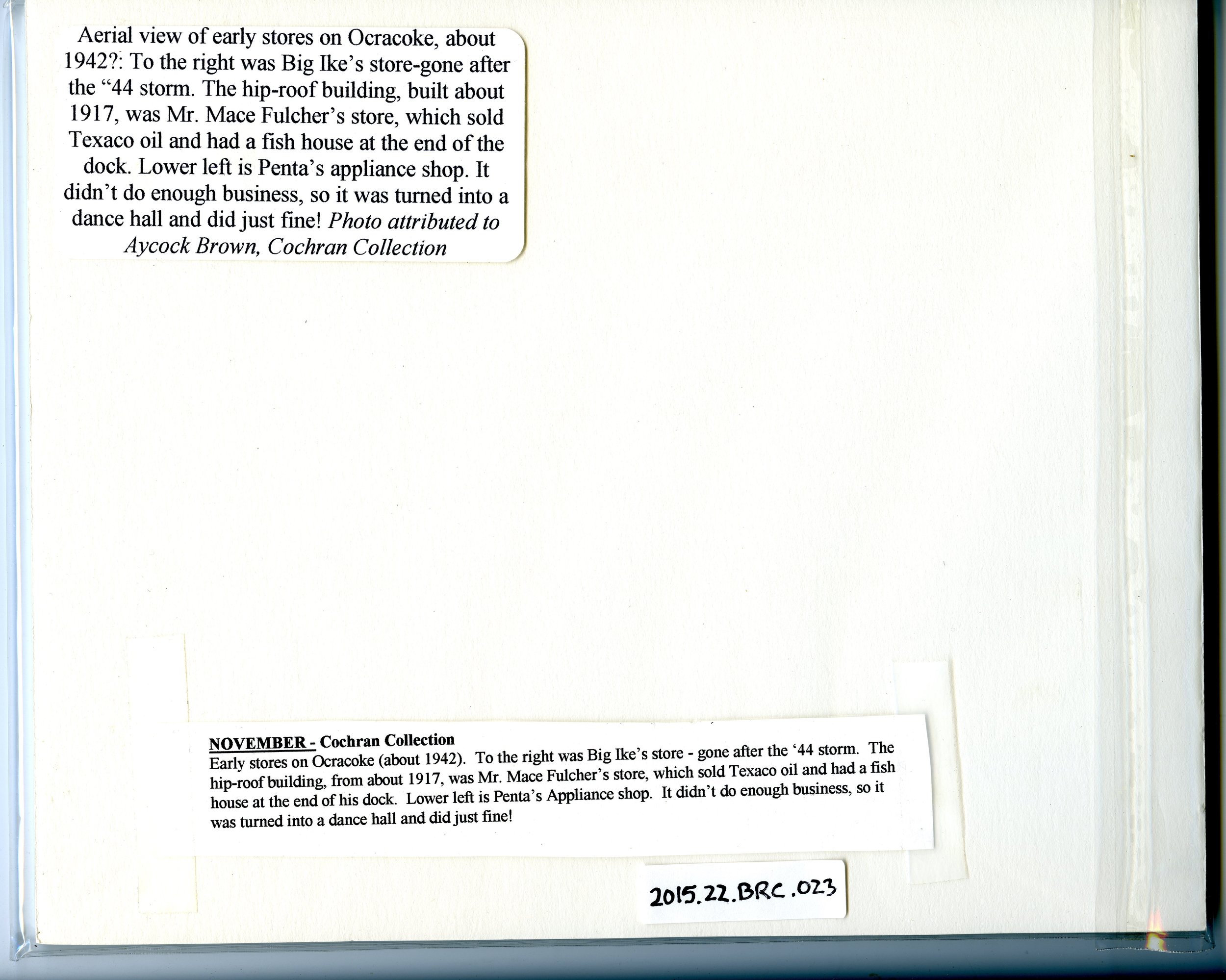

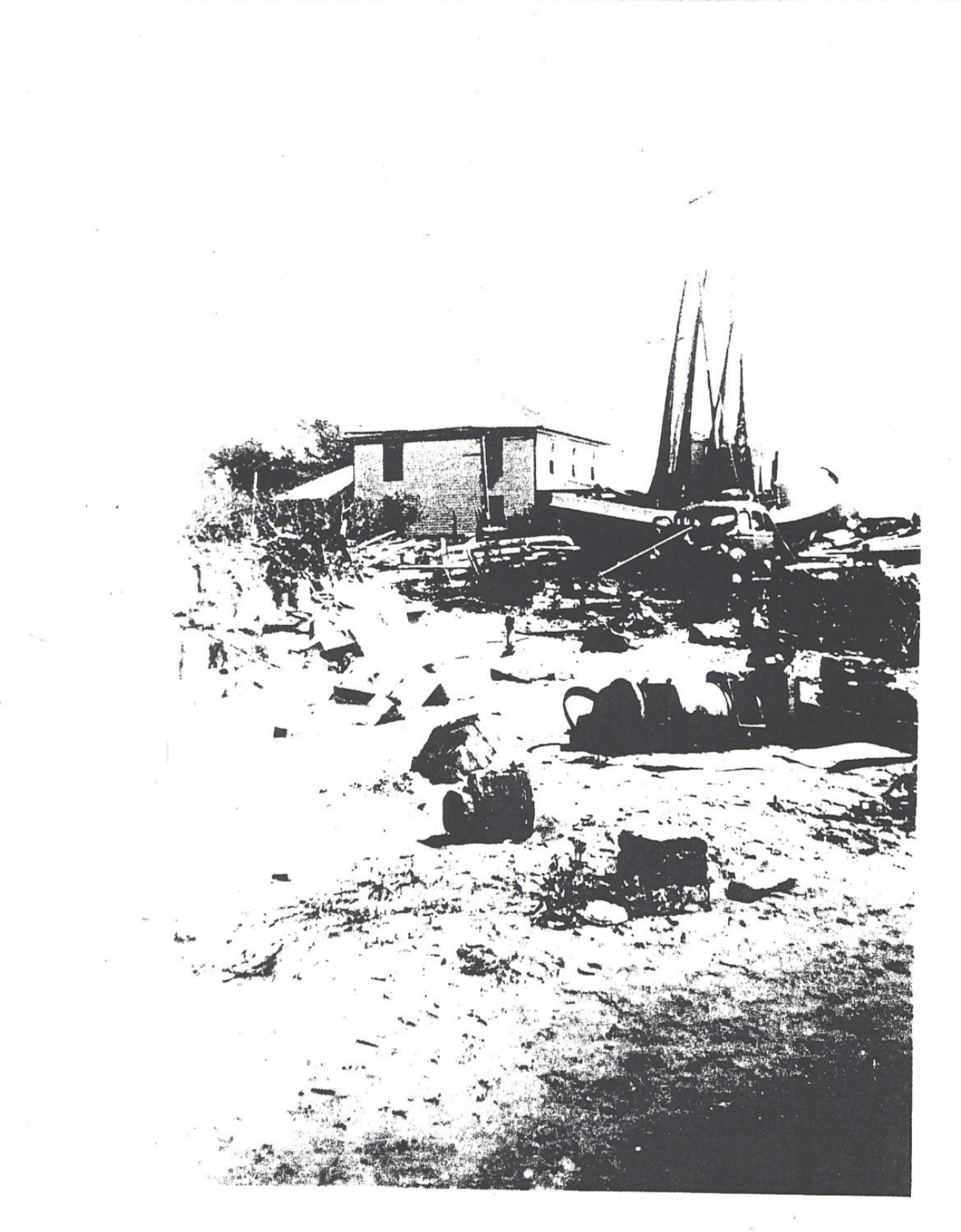

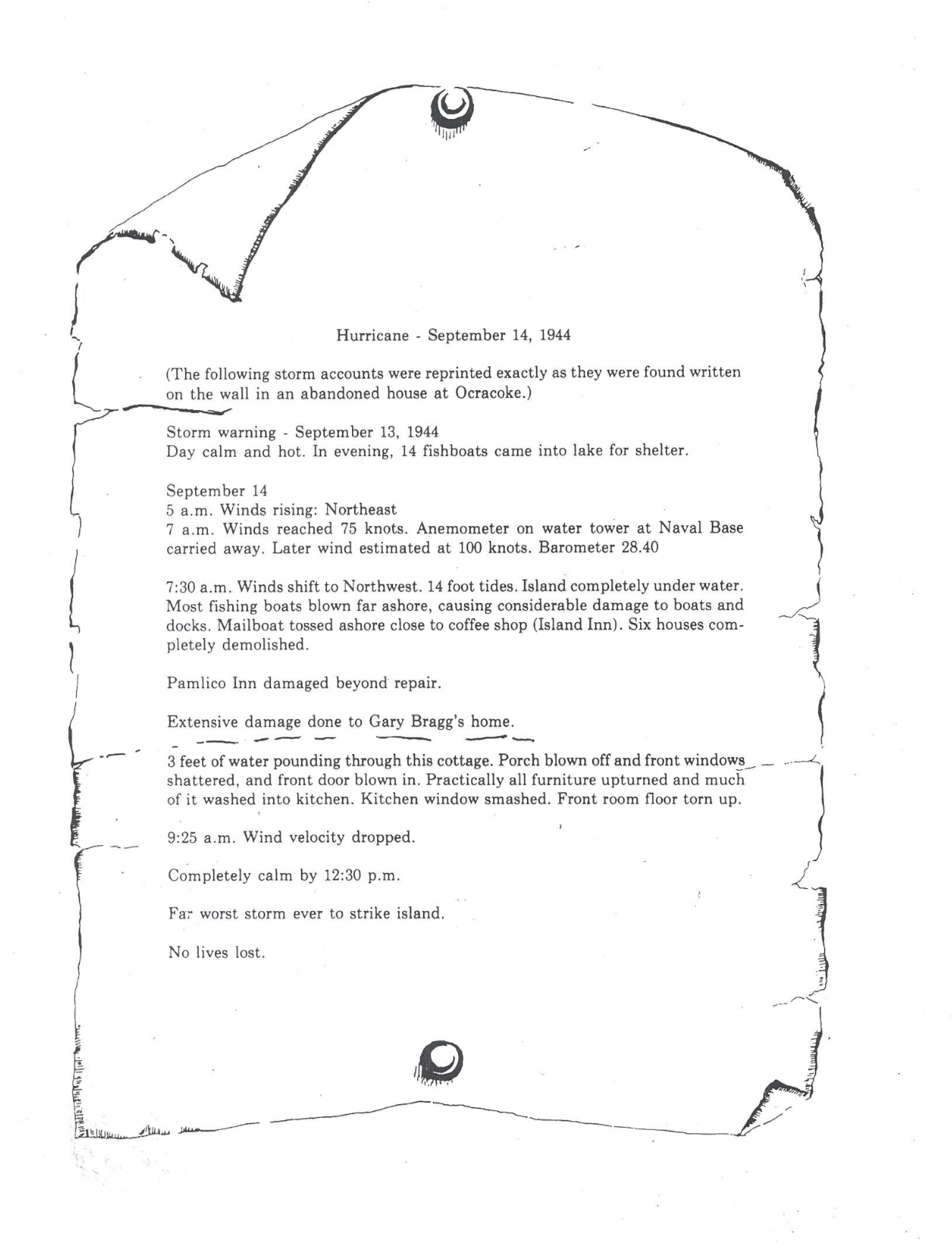

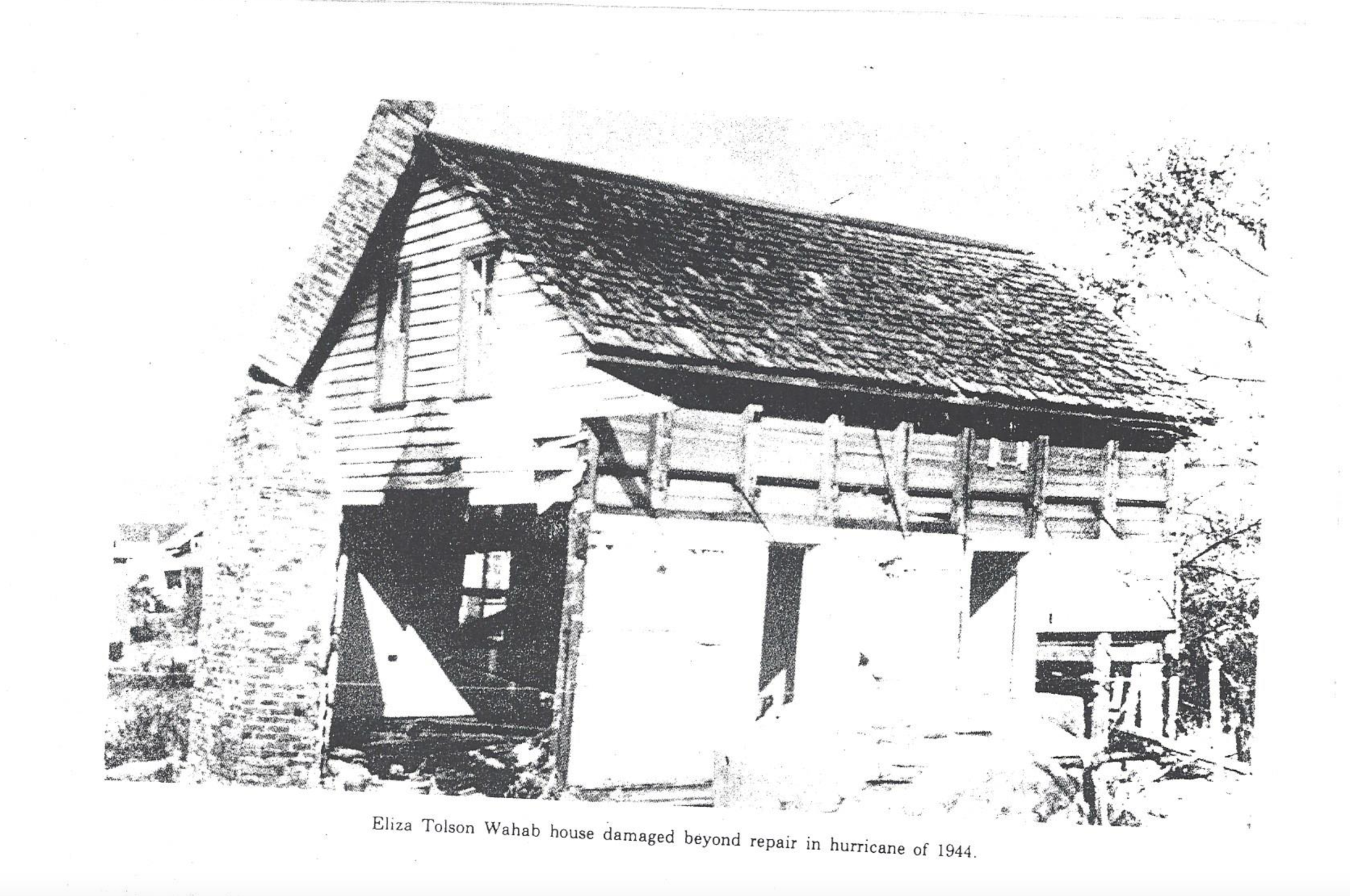

Most of the homes and businesses destroyed by the Great New England Hurricane of 1938 had been rebuilt by the summer of 1944. But the Great Atlantic Hurricane of ’44 again flooded the Northeast, and damage from this hurricane was heavy. In North Carolina, the ’44 storm was called the “worst ever” by some on the Outer Banks, who again watched as the ocean and sound met, surrounding their homes with water. On Ocracoke, the tide rose two to four feet in many houses. As they had done so many times in the past, residents there opened their doors to the rising waters to keep their homes in place. Fish were reportedly trapped under furniture and left behind when the storm passed and the waters receded.

The hurricane moved northward up the banks at about 30 mph on the morning of September 14. At Cape Hatteras, the weather station recorded a barometric pressure reading of 947 mb, the lowest to date for that location. Even though its center remained at sea, the storm’s massive eye wobbled up Hatteras Island and was discernible to the island’s residents. It was reported that the eye was so large that many had time to leave their homes to check on their boats, visit friends, and survey the damages in the area. Some were caught off guard when the hurricane’s eye passed by and winds exceeding 100 mph “hauled around”, blowing from the northwest.

During the storm’s approach, strong southeast winds had filled the sounds with ocean water, backing up all the rivers, creeks, and marshes on the mainland side. Some on Hatteras Island reported that the winds had blown the waters so far west that the sound was left dry for nearly a mile. But as the eye passed and the winds turned around, the waters of Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds rushed back towards the banks, flooding villages from Hatteras to Nag’s Head. Time and again this phenomenon of wind and water recurs with passing hurricanes, each time bringing new potential to reshape the Outer Banks.

The most serious flooding was in Avon. During the 1930’s, the Civilian Conservation Corps had installed miles of fencing on the beach, which collected sand to form a protective barrier. The “sand walls” practically surrounded the towns. When the ’44 hurricane’s west winds pushed the sound into the village, the sand walls became a dike that prevented the waters from escaping. The massive surge could not continue on across the banks to the ocean, and Avon became a deep pool. Residents reported seeing cars and trucks completely covered by the tides. Houses drifted about, sometimes crashing into each other. One young girl, huddled in desperation with her family in a second-story hallway, actually became seasick as her home sloshed about by the tide and wind. Avon was hit hard, as 96 of the town’s 115 houses were severely damaged or washed off their foundations.

Along the northern banks, the pounding northeast winds and waves scoured out the skeletons of forgotten shipwrecks, some of which had been buried for generations. There was heavy damage in Elizabeth City and in Nag’s Head area, some from flooding but much from the storms high winds. At Cape Hatteras winds were estimated at 110 mph (after the anemometer failed), but at Cape Henry, Virginia, the hurricane’s top winds were recorded at 134 mph. The highest gust at that location was estimated at 150 mph. Maximum wind velocities equaled or exceeded all previous records at Hatteras, Cape Henry, Atlantic City, New York City, and Block Island, Rhode Island.

Although only one North Carolinian was killed in the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944, the storm was deadly overall. In the Northeast, 45 more lives were lost, including 26 in Massachusetts. But most tragically, 344 more people died at sea as five ships sank during the hurricane. Two of those lost off the North Carolina coast. The Coast Guard cutters Jackson and Bedloe both capsized and sank while guarding a liberty ship that had been torpedoed near Cape Hatteras. German U-boats were active at that time in attacking Allied vessels that moved along the Outer Banks. The ’44 hurricane provided only a brief interruption in their acts of war.

— Excerpt from North Carolina’s Hurricane History by Jay Barnes, Fourth Edition

Through the Lens