Storm of '33

September 1933

Quick Facts

Storm Type | Cat. 2 Hurricane

NC Landfall | Ocracoke

NC Wind Speed | 125 mph

NC Storm Surge | 11 ft

NC Rainfall | no data

NC Pressure | 28.26 in

Total Deaths | 39

NC Deaths | 21

Total Cost Then | $3,000,000

Total Cost 2009 | $57,818,307

about the storm

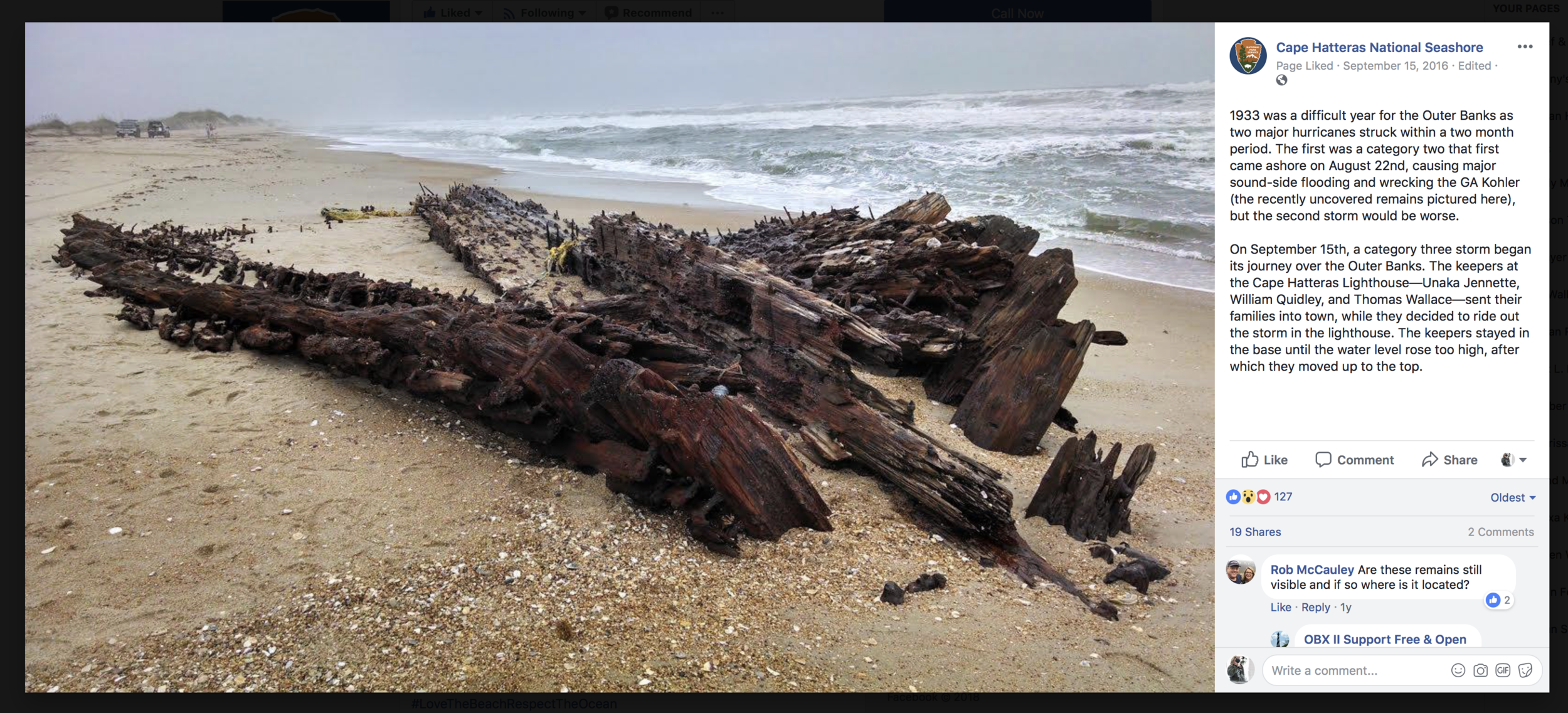

Less than a month after the August storm, another hurricane moved toward the coast. By the morning of September 15, it was 250 miles south of Cape Hatteras, and all indications were that it would cross the North Carolina coastline late that night or early the next morning. Storm warnings were issued, and the few coastal cities that had hurricane plans put them into effect. The American Red Cross, better organized after its recent experience with tragic hurricanes in Florida, urged the Carolina chapters to prepare for a potential disaster.

When the hurricane approached the mainland, it swerved to the north. As it pushed through Pamlico Sound, intense northeast winds forced tremendous quantities of water to surge to the southwest, flooding the river basins of the Neuse and the Pamlico. An unusual phenomenon occurred along the northern banks of the Albemarle Sound when the water was “blown away” to the lowest level ever recorded for that region.

The tremendous storm tide that swept through several down-east communities claimed twenty-one lives and left extensive destruction. The wind driven water remained high on the land until the storm moved up the coast. Then, as if the plug was removed from a bathtub, the water rushed back toward the sea, overwashing Core Banks from west to east and opening Drum Inlet in the process. Winds were recorded at 92 mph at Cape Hatteras, just before the anemometer was destroyed. In Beaufort and New Bern, winds were estimated at up to 125 mph. In some areas, wind-related damage was as severe as the flooding. Countless large trees were downed throughout the east, including the city of New Bern. In an article from the New York Times, a reporter wrote: “New Bern has long been known as the ‘Athens of North Carolina’ because of its so many large and beautiful trees. Now hundreds of these trees are either lining in the streets or leaning grotesquely against the battered houses. Many of the splendid trees of East Front, Broad, Pollack, Johnson, and Craven streets were blown down.”

The flooding in New Bern was the highest ever known and was said to have been about two feet greater than in the storm tide of September 1913. The water reached a height of three to four feet in some streets, and rowboats and skiffs were used to evacuate people from buildings that were completely surrounded by water. The tide rose a foot above the tallest piling on the Coast Guard dock, and the dock was wrecked and washed away. The cutter Pamlico was unharmed, however, even though it was moored to the dock at the time.

The Neuse River bridge that linked New Bern and Bridgeton on U.S. 17 was washed out at about 1:30 A.M. on September 16. A three-quarter-mile-long section was taken out by the surging waters of the Neuse, and piece3s of the bridge were scattered along the shore for miles downriver. Two stalled automobiles were believed to have been stranded on this section, but their occupants were able to escape the bridge before it collapsed. Damage was also reported to the Norfolk and Southern railroad trestle and the Trent River bridge. Several Box-cars were dumped into the Neuse when the Atlantic Coastline Pier caved in.

One unusual story from the storm of ’33 came from the New Bern area. The roof of Mrs. Sam Smallwood’s boathouse was blown off by fierce winds. It landed right side up, a quarter of a mile downriver, with Mrs. Smallwood’s boat, which had been suspended from the rafters, still intact. The boat was retrieved the morning of the storm and was used to take Mrs. Smallwood to high ground.

The damage in New Bern alone was more than $1 million. Many homes and businesses were severely damaged by both high water and winds. Several lumber factories were destroyed. The rising saltwater reached the region’s farmlands, and damage was heavy to unharvested corn, cotton, and sweet potatoes. In many locations, tons of tobacco stored in barns were destroyed when they became soaked by heavy rains and rising floodwaters. But by far, the greatest loss and suffering came to those who lived near the water and made their living from the sea. Carteret County was hard hit by the storm, and remote communities down east were devastated.

The Beaufort News reported the following events the week following the storm:

The oldest citizens here in Beaufort have told the News that it was the most devastating storm that they have seen in the past four score years. It was not merely a bad wind that reached gale force for just a few minutes; the disastrous hurricane swept Carteret for more than twelve hours without ceasing for even a few minutes. From early Friday morning rain began falling and this continued unremittingly until about day break Saturday morning.

This terrific tropical hurricane which swept up the Atlantic coast Friday seemed to have hit Carteret near Beaufort Inlet, striking Beaufort and Morehead City first, the continued with its destructive force on to Merrimon, South River, Likens, Roe and Lola, with all other communities in eastern Carteret getting their shares of the devastating tempest…. Within Carteret County alone there was a property loss of at least a million dollars, eight people were drowned and scores left homeless, hundreds without food and more with barely enough clothing to cover their bodies. Thousands of domestic and wild animals perished in the water and if they were not removed and buried decomposition will result in stench and disease. In the villages where homes and other buildings were wholly or partially demolished, men, women and children by the score stuck nails in their feet and have cuts and bruises and sprains across their bodies. Only a very small percentage have received medical attention and been inoculated with tetanus antitoxin. Sanitary conditions in the stricken area are terrible, and epidemics will in all likelihood ensue if the people do not cooperate wholeheartedly with the sanitary engineers of the Stet Department of Health.

Captain Jim Hamilton and his three sons, Nelson, Charlie, and Ralph, all drowned in Long Bay when their twenty-foot skiff capsized in the storm. Like countless other fishermen before them, they had left their home in Sea Level with no knowledge of the impending weather. Their expedition quickly turned tragic as their small boat was no match for the furious seas.

In the down-east community of Merrimon, the tide was estimated at “fifteen or sixteen feet.” Only four out of thirty houses remained after the tides overwashed the area. The Carraway family endured a horrible ordeal when their house collapsed during the storm. The entire family huddled together as a blast of wind tore down the structure, pinning them in the wreckage amid the rising tides. Mr. Carraway escaped with the help of his son George, but his wife Freda was trapped under the debris. Those who escaped were forced to flee to higher ground when the tides continued to rise, but Freda remained under the house where she apparently drowned.

At nearby Cedar Island, about eight families endured the hurricanes, and almost all of their homes were washed off their foundations or severely damaged. In his book” Sailing with Grandpa”, Sonny Williamson offers a detailed account of the scene as recorded by Captain John Day and his wife Adelaide. Day had come to Cedar Island by boat to check on his relatives in the remote community. Virtually every structure suffered damage in the storm, and the bewildered residents struggled to simply survive in the first few days following their ordeal.

After the hurricane passed, the local director of the Red Cross, Frank Hyde, launched a relief mission to the down east villages. No communication with the isolated hurricane victims was possible, so this voyage would provide the first news of the conditions in these areas. Thirty “orders” of food and supplies were prepared for the relief effort, which was assisted by the Coast Guard. Hyde left Fort Macon for Core Sound early Monday morning, two days after the hurricane’s arrival.

The mission reached Lola, on the southern end of Cedar Island, by late morning. James Whitehurst, a reporter for the Beaufort News, was traveling with Hyde and filed the following report:

Upon arriving on shore we were conducted through a throng of half-clothed bewildered people who looked upon us with overjoyed eyes. One young woman with a baby-it appeared to be her first-cried with joy. Every person seemed to have stuck nails in their feet or had cuts and bruises about their bodies. The last food in Lola had been consumed for breakfast, and this had been far from sufficient.

The homes had been washed from their foundations, windows had been blown out, roofs and roofing wrenched from the tops of the structures. Wreckage was strewn from one end to the other. Few of the people had shoes on, and virtually everyone had on all the clothing they had been able to salvage.

When the Coast Guard boat carrying Hyde moved to the northern end of the island, its passengers found even greater destruction in the village of Roe. Eight or ten homes were described as totally destroyed, and only one was “fit for winter.” Most of the homes had floated haphazardly with the tides, and many suffered structural damage. Thick mats of mud, grass, and debris filled several houses and littered the branches of nearby trees.

At South River, similar floods struck late Friday night. The Louis Cannon family narrowly escaped drowning when their home collapsed in the storm. They had gathered in their attic when waters rushed into the first floor. They eventually escaped by clinging to the rooftop of the demolished house until they became caught in the top of a grove of trees. There they rode out the storm until the waters receded.

The home of William Cannon became a refuge for other South River residents who were forced to flee their homes. The Cannon residence was on higher ground than many other houses, and frightened neighbors and relatives made their way there when the floods moved in. Ultimately, more than fifty people were sheltered in the house. Many stayed through Saturday, until they were able to return to what was left of their homes.

One of the great tragedies of the ’33 storm struck the family of Elijah Dixon, who were staying in a two-story home near Back Creek when the hurricane hit. Dixon, his wife Ellen, and their eight-year- old daughter Hazel, three-year-old son James, and nine–month-old daughter Elva Marie were all plunged into the raging waters when the house washed into the Back Creek. The family tried desperately to cling to the broken fragments of the rooftop. With his young son around his neck, Dixon jumped into the dark waters to rescue his wife, who was still clinging onto baby Elva. In the darkness and confusion, the infant slipped from her arms and drowned. As the weary group again gathered on the roof, they realized that young Hazel was missing. Reeling from his double tragedy, Dixon still managed to grasp a large branch when the rooftop was swept into a grove of trees. There the battered family remained until later Saturday afternoon, when they were rescued.

The tragedies of the 1933 hurricane were spread throughout numerous downeast communities. At Oriental, Vandemere, Bayboro, and Arapahoe, local newspapers reported that “hardly a building was left intact.” From Ocracoke, there was a report that ”four feet of water had covered the island.” As the hurricane’s storm surge pushed over Ocracoke, residents had prepared their homes by removing floorboards to prevent the rising tides from washing their houses “off the blocks.” Many rode out the hurricane in their attics, and some were forced onto their rooftops.

At the Green Island Hunt Club at the eastern end of Ocracoke, nine people took refuge as the storm approached. The two story clubhouse was rocked by pounding surf, and by midnight, “the ocean was breaking into the kitchen.” As the first floor filled with water, the occupants gathered on the second floor, which the group was forced to crawl through a high window onto the roof, where they rode out the storm. The structure pitched and rolled like a boat, and the constant up and down motion washed away the foundation, digging a deep hole in the sand. The frightened men and women held desperately to the rooftop through the gusting winds and strong surf until, at daybreak, the storm passed.

As the tides receded, the survivors climbed down off the clubhouse. To their amazement, the wave action had dug the house so far down that the second floor windows were level with the ground. The fishermen were also surprised to see their boats cast upon a nearby beach. During the storm, these small craft were blown into the sound, but when the hurricane passed and the winds shifted, they were blown right back, suffering little damage.

The September hurricane of 1933 left many scars on the North Carolina coast. In all, twenty-one were dead and damage estimates topped $3 million. The Red Cross identified a nine-county region with a population of 120,000 as the area of greatest suffering. Their survey indicated that 1,166 buildings had been totally destroyed and 7,244 severely damaged. The Red Cross gave aid to 1,281 families, many of whom received help with the rebuilding of their homes. This effort helped temper the anguish caused by one of the most tragic storms in North Carolina history.

— Excerpt from North Carolina’s Hurricane History by Jay Barnes, Fourth Edition

Through the Lens