Hurricane Hazel

October 1954

Quick Facts

Storm Type | Cat. 4 Hurricane

NC Landfall | SC/NC Border

NC Wind Speed | 127 mph

NC Storm Surge | 18 ft

NC Rainfall | no data

NC Pressure | 27.67 in

Total Deaths | 600

NC Deaths | 19

Total Cost Then | $350,000,000

Total Cost 2009 | $3,259,892,193

ABOUT the storm

Hazel (October 15, 1954) Hazel began, like many other hurricanes, as a trough of low pressure over the warm waters of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. On October 5, 1954, the small storm was identified just east of Grenada and was observed on west-northwest track that would take it through the Grenadines. Winds were clocked at 95 mph, and the small island of Carriacou was the first to suffer from Hazel’s winds and tides.

At the weather Bureau’s Miami office, veteran chief forecaster Grady Norton was working twelve-hour days plotting Hazel’s course. Tragically, Norton suffered a stroke on the morning of October 9 and died later the same day. The Weather Bureau scrambled to pick up where Norton had left off, following the daily reports of the growing storm. Although he had been warned by his doctor to avoid the long hours, Norton had ignored his medical condition out of concern for the hurricane’s potential destruction. Following his death, the bureau did not skip a beat. Norton’s assistant issued timely warnings and made urgent phone calls to coastal officials as the storm approached the Carolinas.

Hazel continued to draw energy from the warm Caribbean waters and intensified as it curved northward toward Haiti. During the early morning hours of October 12, the well-organized storm slammed into the Haitian coast, raking over both the southern and northern peninsulas.

The eye of the hurricane passed about ninety-five miles east of Charleston, South Carolina, at 8:00 A.M. on October 15. About the same time, the outer fringes of the storm first touched the U.S. coastline near North Island, South Carolina. Finally, between 9:30 and 10:00 A.M. Hazel’s ominous eye swept inland very near the North Carolina-South Carolina border. It was there that its most awesome forces were unleashed, although the destruction continued as the hurricane barreled across the state.

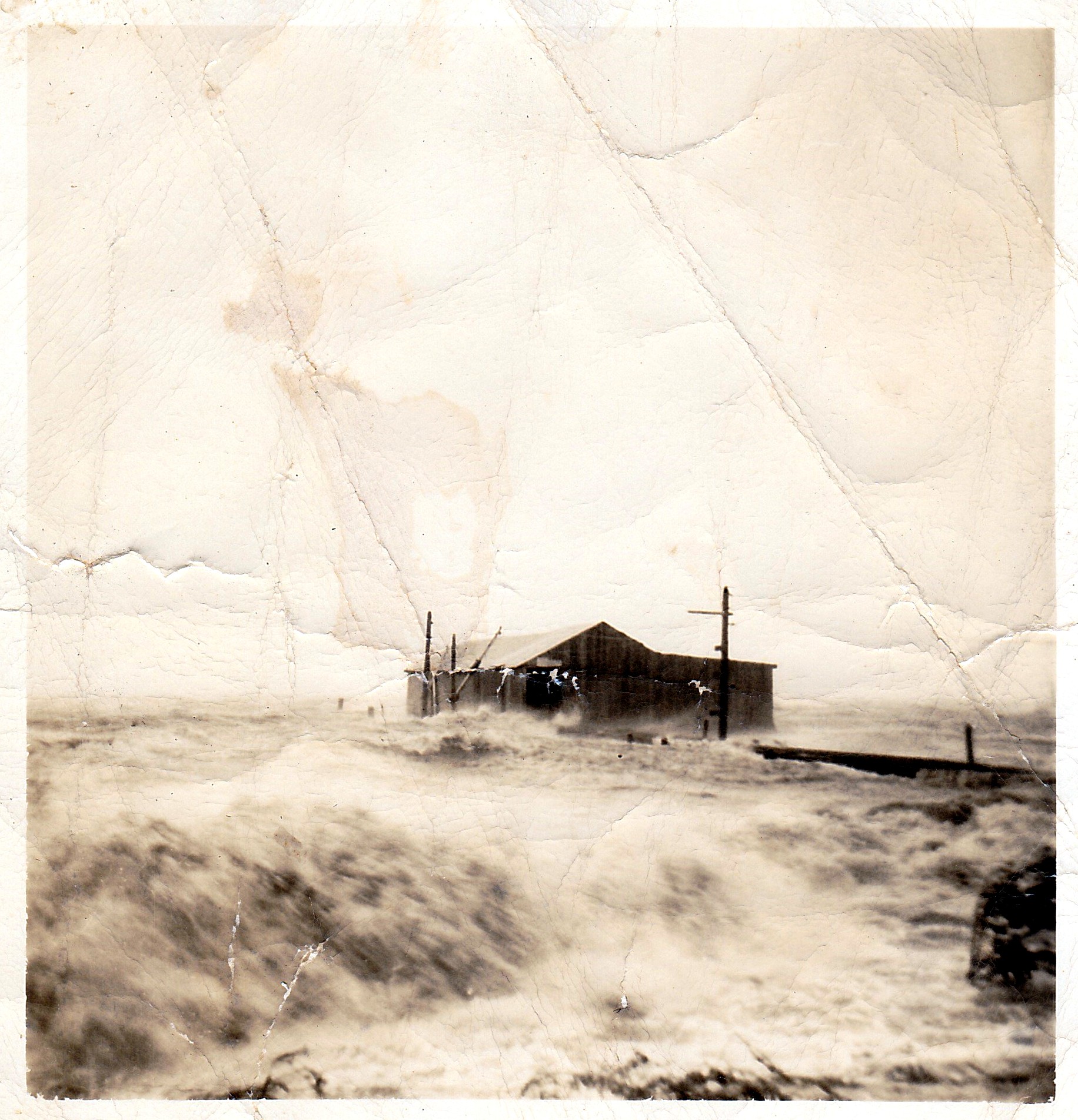

The storm surge that Hazel delivered to the southern beaches was the greatest in North Carolina’s recorded history. The flood reached eighteen feet above mean low water at Calabash. Hazel’s surge was made worse by a matter of pure coincidence- it has struck at the exact time of the highest lunar tide of the year, the full moon of October. Local hunters refer to this as the “marsh hen tide,” a time when high waters tend to flush waterfowl out of the [protective cover of marsh grass. Hazel’s storm tide may have been boosted several feet by the unfortunate timing of its approach.

Hazel’s violent winds hacked or toppled countless trees across eastern North Carolina. In the aftermath of the storm, some sections of highway were littered with “hundreds of trees per mile.” Some were uprooted and tossed about, and others were snapped off ten to twenty feet above the ground. In the city of Raleigh, it was reported that an average of two or three trees per block fell. Many landed on cars, homes, and other structures, and power lines were left tangled and broken. Dozens of other cities and towns in the eastern half of the state faced similar losses.

Heavy rains fell from northeastern South Carolina to central North Carolina and Virginia. The areas that recorded the greatest rainfall amounts were all on the western side of the storm track, and many eastern locations received as little as one inch. At least ten weather stations in North Carolina established new twenty-four-hour records for rainfall. These records included about 6.5 inches in Burlington, High Point, and Lexington and 9.72 inches in Carthage, located in the sandhills area of the state. A U.S. Geological Survey rain gauge at Robbins, several miles north of Carthage, measured 11.25 inches. Several locations in northern Virginia recorded more than 10 inches, and new rainfall records were established all along Hazel’s northern course.

In North Carolina, the destruction left by Hazel was likened to the battlefields of Europe after World War II. Evidence of the storm’s violent winds stretched across the state, leaving residents with the task of cleaning up virtually every city street and country road in the eastern half of the state. And the storm tide that swept over the Brunswick and New Hampshire beaches brought massive destruction to the coast and was, by all accounts, unparalleled in Tar Heel history.

When Hazel made landfall at Little River, near the North Carolina-South Carolina state-line, its deadly storm surge and intense winds reached their peak. At Myrtle Beach, hurricane-force winds began round 6:00 A.M. and continued to intensify until the eye reached the coast at 9:20 A.M. The South Carolina beaches were battered by northeast winds estimated at 130 mph and waves that crested at thirty feet. Hardest hit were locations near the point of landfall, which included Garden City, North Myrtle, Windy Hill, Cherry Grove, and Ocean Drive. Throughout this stretch of coastline, storm surge levels ranged between fourteen and seventeen feet above mean low water. Although the destruction in South Carolina was greatest on the northern beaches, homes and piers were damaged as far south as Georgetown. Hazel killed one person in South Carolina and brought $27 Million in property damages to the state.

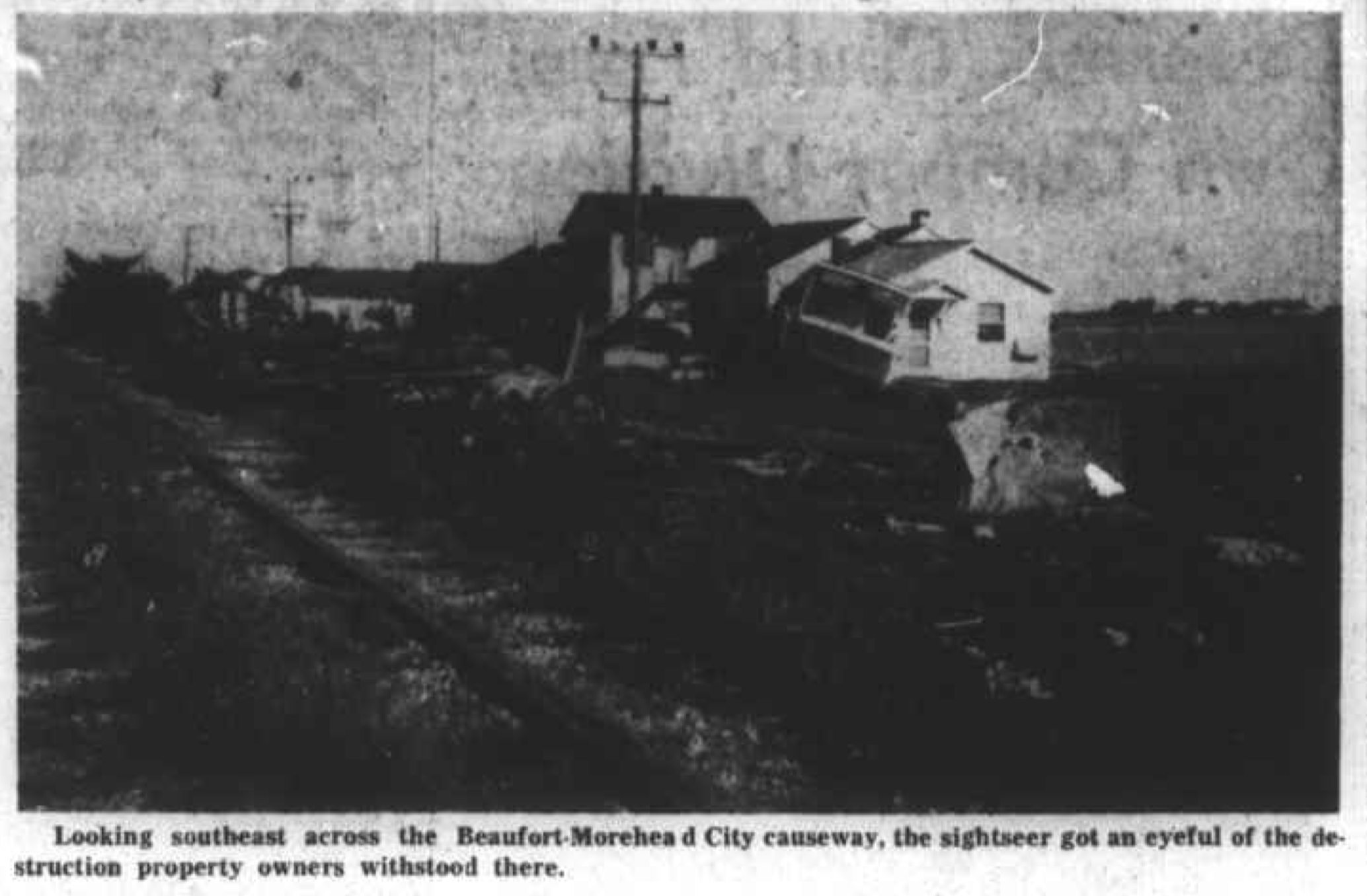

In Carteret County, 120 miles north of where Hazel made landfall, residents witnessed the worst hurricane in many years. Hundreds of citizens took refuge in the Morehead City Town Hall and the county courthouse in Beaufort. Damage was extensive in several locations near the water, including Atlantic Beach and the causeway that joins Morehead City and Beaufort. Property damages were reported at $2 million, but fortunately there were no reports of deaths or serious injuries. Thirty-five homes were destroyed, and scores more suffered minor damage.

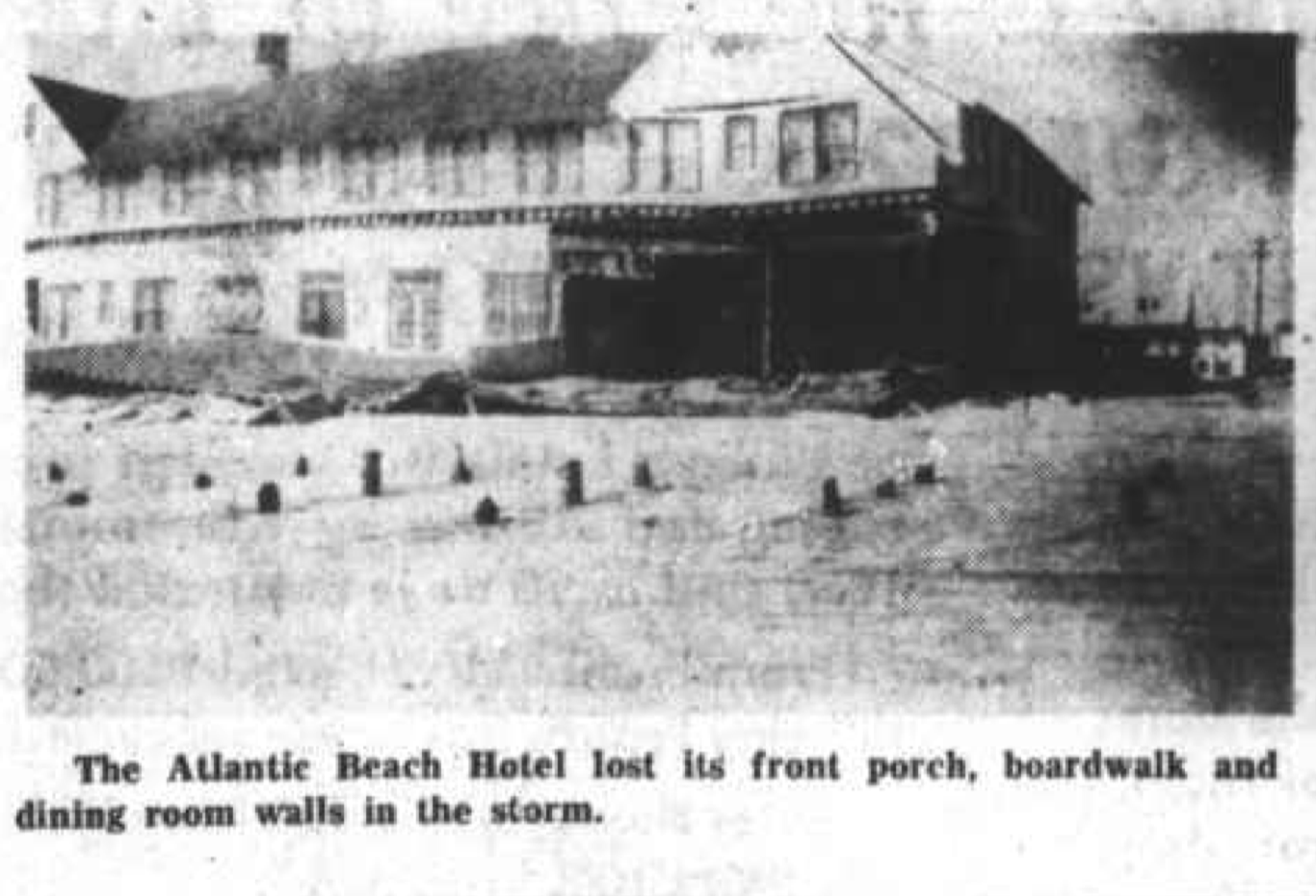

In Atlantic Beach, Hazel’s storm surge pounded the boardwalk area to rubble. Twenty-foot waves washed away a section of the Atlantic Beach Hotel. At King Hotel, undermining the structure. The triple S Pier was battered by the surf, and its tackle shop was badly damaged. After the storm, only 200 of the pier’s 1,000 feet remained. The old beach highway that connected Salter Path and Emerald Isle was swept away in two places. In these areas, Bogue Sound connected with the ocean, but only briefly, until heavy equipment was brought in to fill the overwash.

In Morehead City, a fish house, dwelling, and skating rink were washed from their foundations. Large glass windows were smashed and trees were toppled by wind that gusted to near 100 mph. At the peak of the storm, surging waters flooded the basement of the Morehead City Hospital. For hours, fire trucks pumped the water out so that basement facilities could continue to be used. Nurses in the basement worked with water up to their knees, scrambling to remove patients and save equipment.

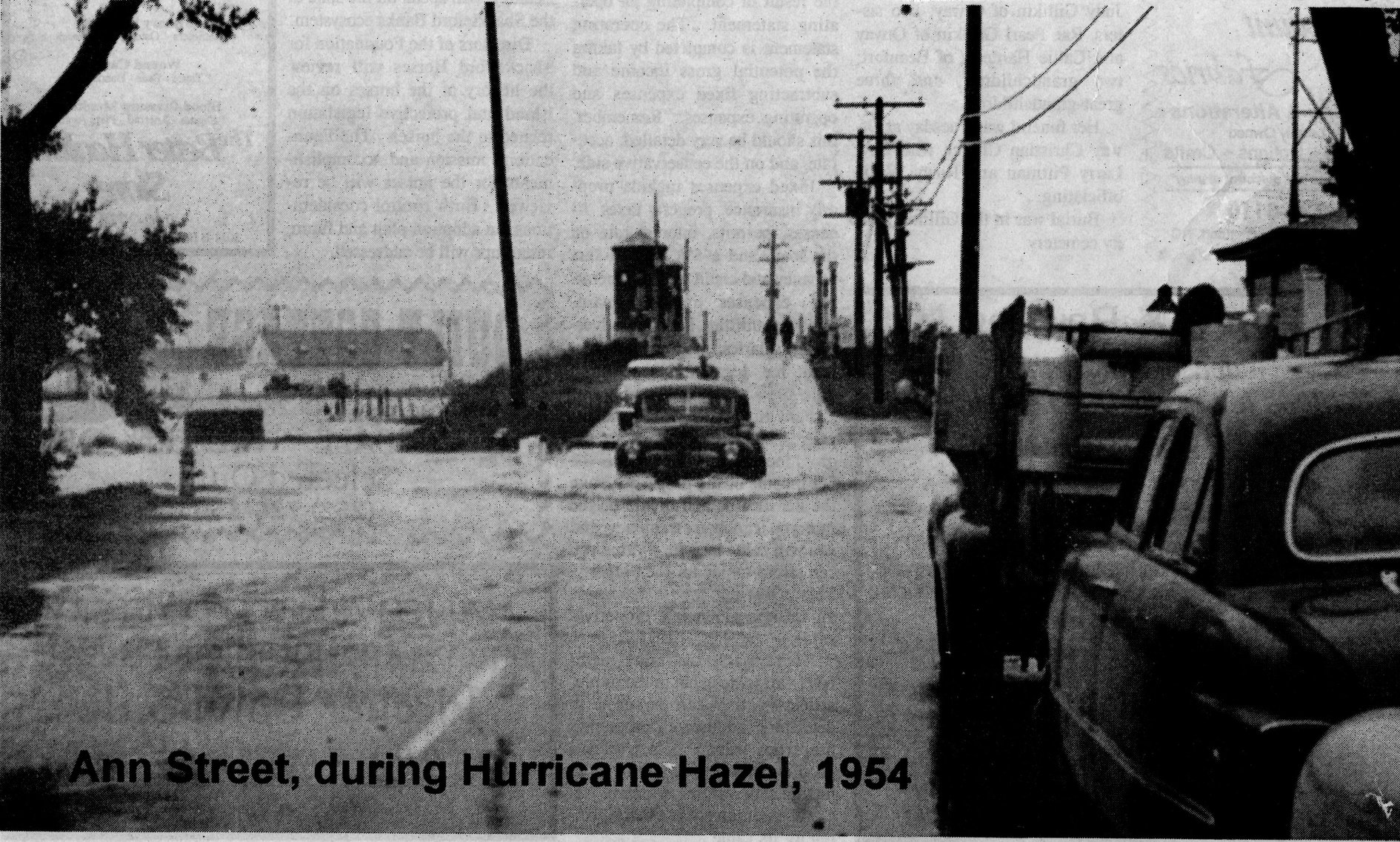

Tony Seamon of Morehead City witnessed the effect Hazel had on the county. He and his father ventured downtown during the storm. “Daddy wanted to check on the restaurant,” Seamon recalled, referring to the Sanitary Restaurant, which his father owned. “We drove down Twentieth Street and the wind whipped the water across the road. We came to the old wooden picket bridge and it was submerged. The only way we could drive through that water was to open both car doors and let the water come through.”

As they reached downtown Morehead, Seamon’s dad asked him to investigate the damage to the restaurant. “He told me, you got to get out and look inside,” Seamon remembered. After one failed attempt to wade through the waist-deep water, he tried again to make it to the restaurant. “The current through the street was like a river. I eventually went under swimming to avoid the wind. When I got to the restaurant, I could look through the door and see all the tables and chairs floating around. Daddy had made the decision to cut holes in the floor to equalize the pressure. At least the whole place didn’t float away.”

After the hurricane passed, the Sanitary Restaurant was cleaned up and put into service as a feeding center. The Red Cross set up generators to provide power, food was brought in, and coupons were issued for meals. Work crews involved in cleanup efforts were fed round the clock until power was restored to the area and things returned to “normal.”

Other portions of Carteret County were hit hard by the storm. Several homes along the Morehead-Beaufort Causeway were totally wrecked, and their debris was piled high in the middle of highway 70. Huge waves rolled across the causeway for hours, washing away homes and depositing small skiffs and one large cruiser in the roadway. Several cars were abandoned by their owners on the east side of the Beaufort bridge when the unwary motorists became trapped by the hurricanes surging tide. The cars choked when water completely covered their engines, and the drivers were forced to wade through the tide to safety.

In Beaufort, the downtown businesses along Front Street suffered heavy losses. Every store was flooded with seawater, which covered the entire street to a depth of three feet. Gusting winds caused plate-glass windows in numerous stores to shatter, resulting in even greater damage from wind-driven rain. City Appliance Company, Bell’s Drug store, and Merrill’s Men’s Store were among the hardest hit. Numerous small boats were washed into the streets, and at least four cabin cruisers sank in Taylor’s Creek. The highest water in Beaufort occurred at 11;15 A.M., when the barometer fell to its lowest point (for Carteret County) of 984 mb. The tides in Morehead reached their peak an hour later, around noon.

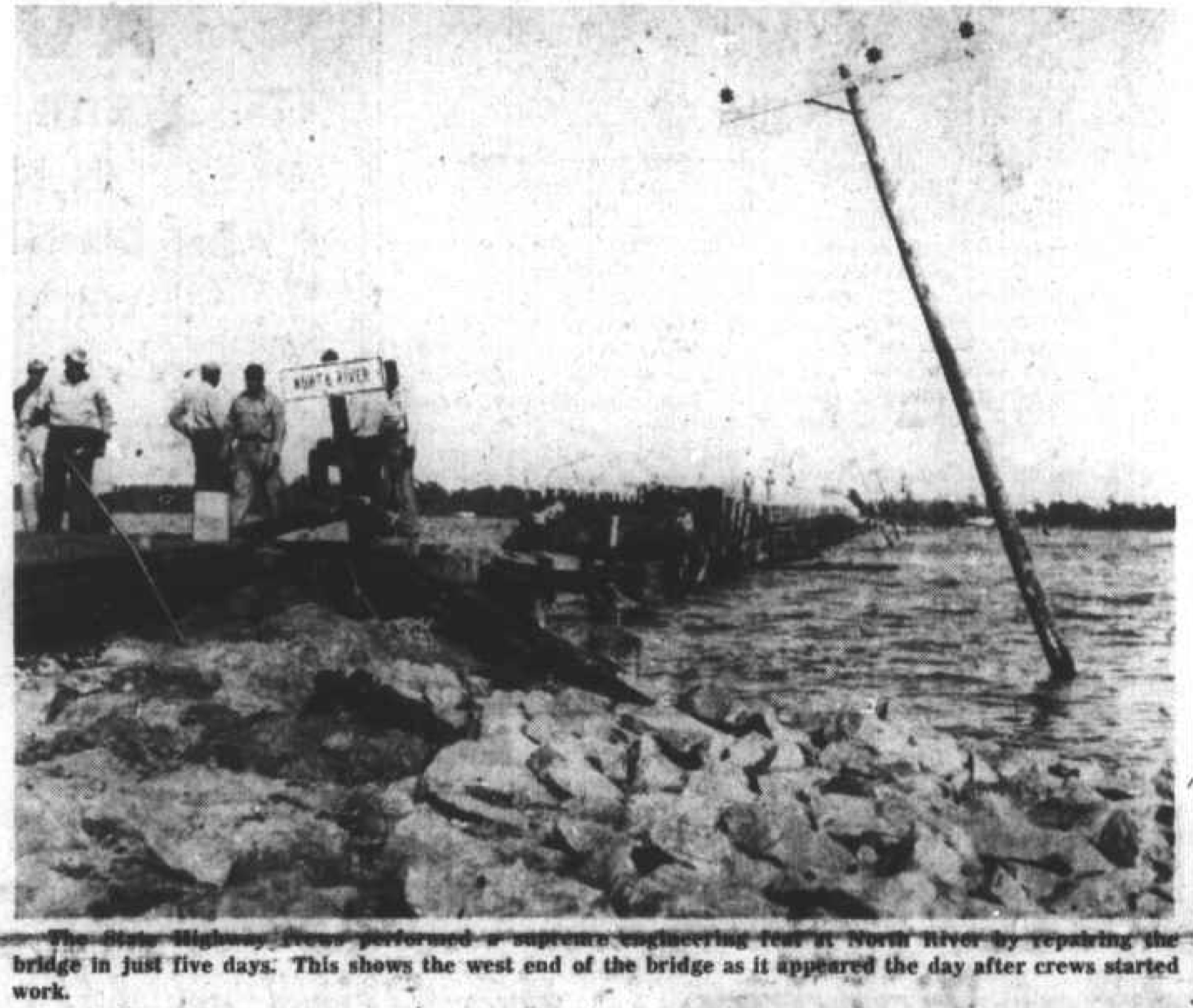

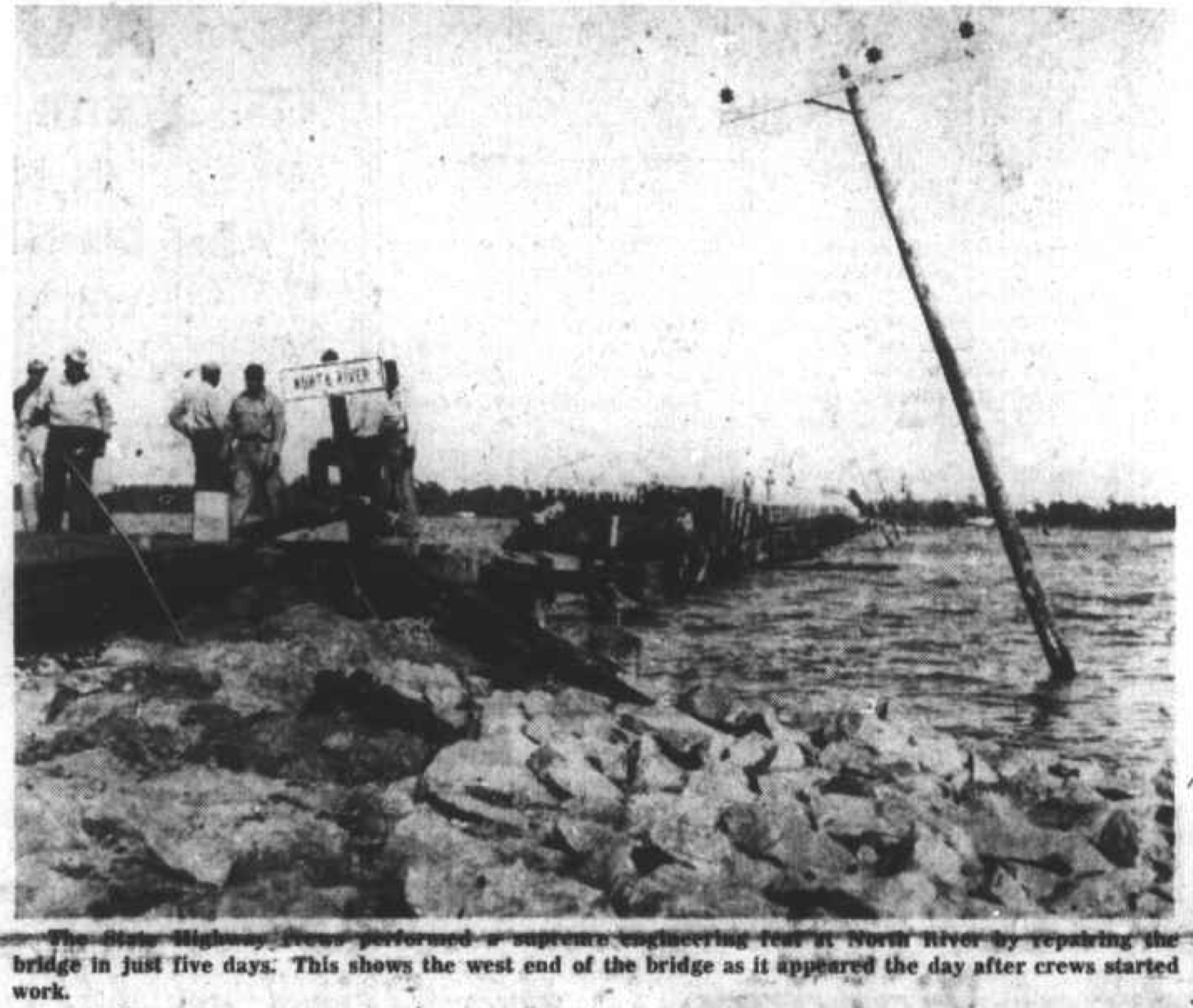

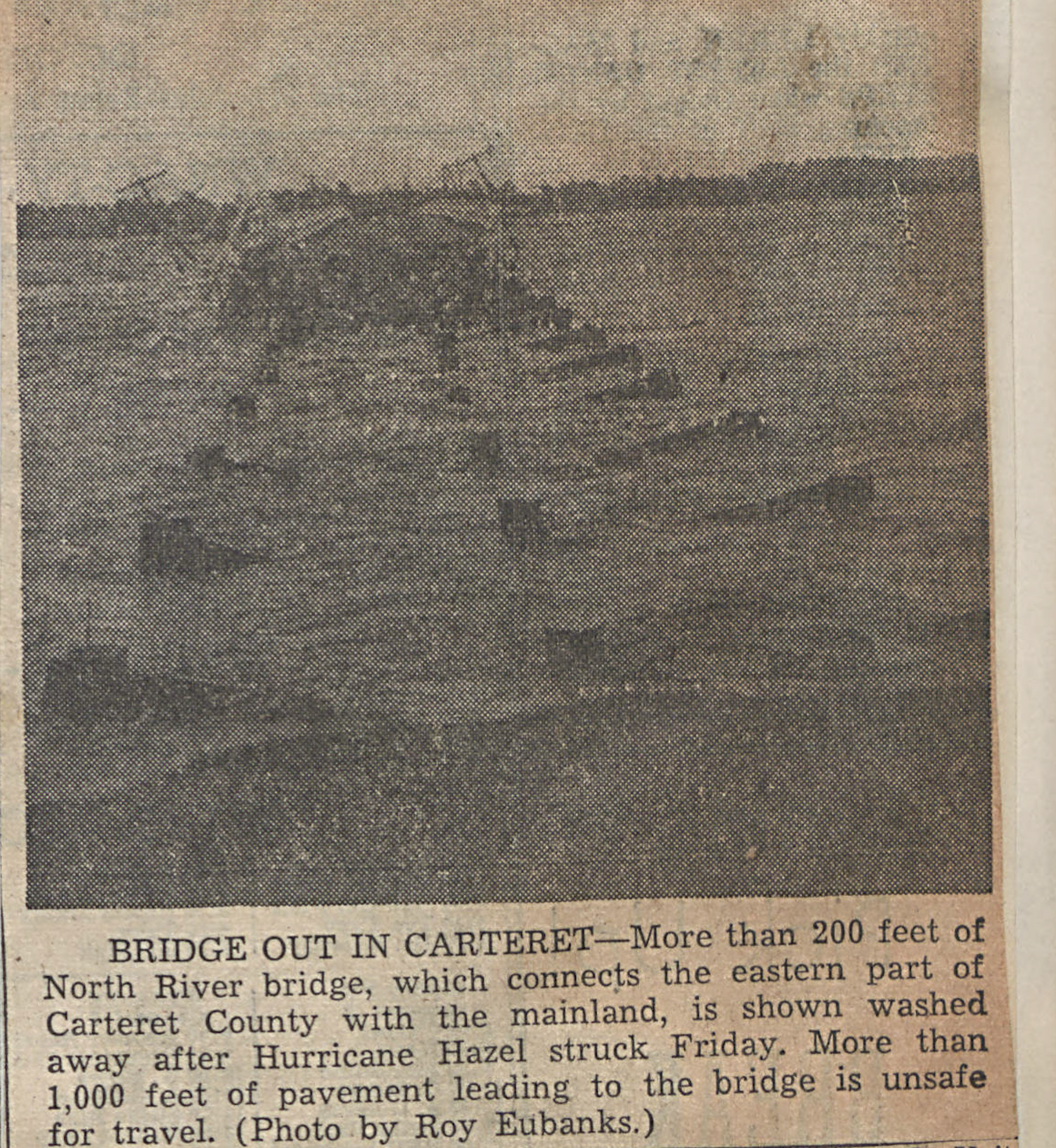

Across the county, Hazel battered homes, boats, and utilities. Many roofs that had just been reshingled after hurricane Edna were stripped again by gusts of 90-100 mph. Power lines and poles were tangled, and communications were cut. A section of the North River Bridge was washed away, but thanks to rapid work by state highway crews, the bridge was repaired just five days after the storm.

Although the Pamlico and Albermarle Sounds region was far from Hazel’s center as it tracked through the state, numerous communities throughout the area suffered serious flooding. The Outer Banks north of Ocracoke were not severely affected, but cities such as Washington and Belhaven saw extensive damage from the rising tides. New Bern, Edenton, and Elizabeth City also reported flooding. But across a wide portion of inland North Carolina, far from the effects of the tides, Hazel’s powerful winds brought significant destruction to more than two dozen counties.

By most accounts, it was the most destructive hurricane in Tar Heel history. In North Carolina, the toll was heavy: 19 killed and over 200 injured; 15,000 homes and structures damaged: 30 counties with major damage: and an estimated $136 million in property losses. But when the hurricane’s effects in North Carolina are combined with those of the other states, as well as with those of Canada and Haiti, the numbers climb: over 600 dead and an estimated $350 million in property damage. And of course, the damages are in 1954 dollars.

The great hurricane of October 1954 became a benchmark in the lives of many North Carolinians who endured the storm. From Holden Beach to Henderson and everywhere in between, any time the topic of hurricanes is raised, stories about Hazel are sure to follow. Stories of heroic rescues and tragic losses are well remembered, as are testimonials to the awesome destructive forces the storm displayed. Hazel ranks as one of the most catastrophic hurricanes to strike the United States in the twentieth century. Fortunately, storms of its magnitude are relatively rare events, and few other hurricanes deserve comparison with it. But much to the dismay of the people of eastern North Carolina, the active 1954 hurricane season that had spawned Carol, Edna, and Hazel was merely a prelude to the 1955 season, when three more storms would strike the state.

— Excerpt from North Carolina’s Hurricane History by Jay Barnes, Fourth Edition

Through the Lens